010! Gaming the system: industry plants, AI and our search for authenticity

How and why we became so skeptical of music

Hi everyone, thanks for your patience again - LIFE! I’m back with more inside baseball chat this time. I’ll be delivering music and visual content in the next week or two as well. If you like this post, please share it and subscribe!

Pop music is so back. The past six months have been a chaotic and exciting time on the US charts: we’ve had drama (Drake vs Kendrick), honest-to-god bangers (Charli XCX), new stars (Chappell Roan), melody-driven singalongs (Sabrina Carpenter), interesting musical choices (Tommy Richman), Black country stars (Shaboozey) and acts finally getting a long-deserved hit (Tinashe). It’s been fun, and it’s been maximalist, as pop should be.

Billboard reported that the average weekly US units of a Hot 100 #1 have doubled between Q1 and Q2 this year, and almost tripled since 2022. That’s some healthy cultural staying power.

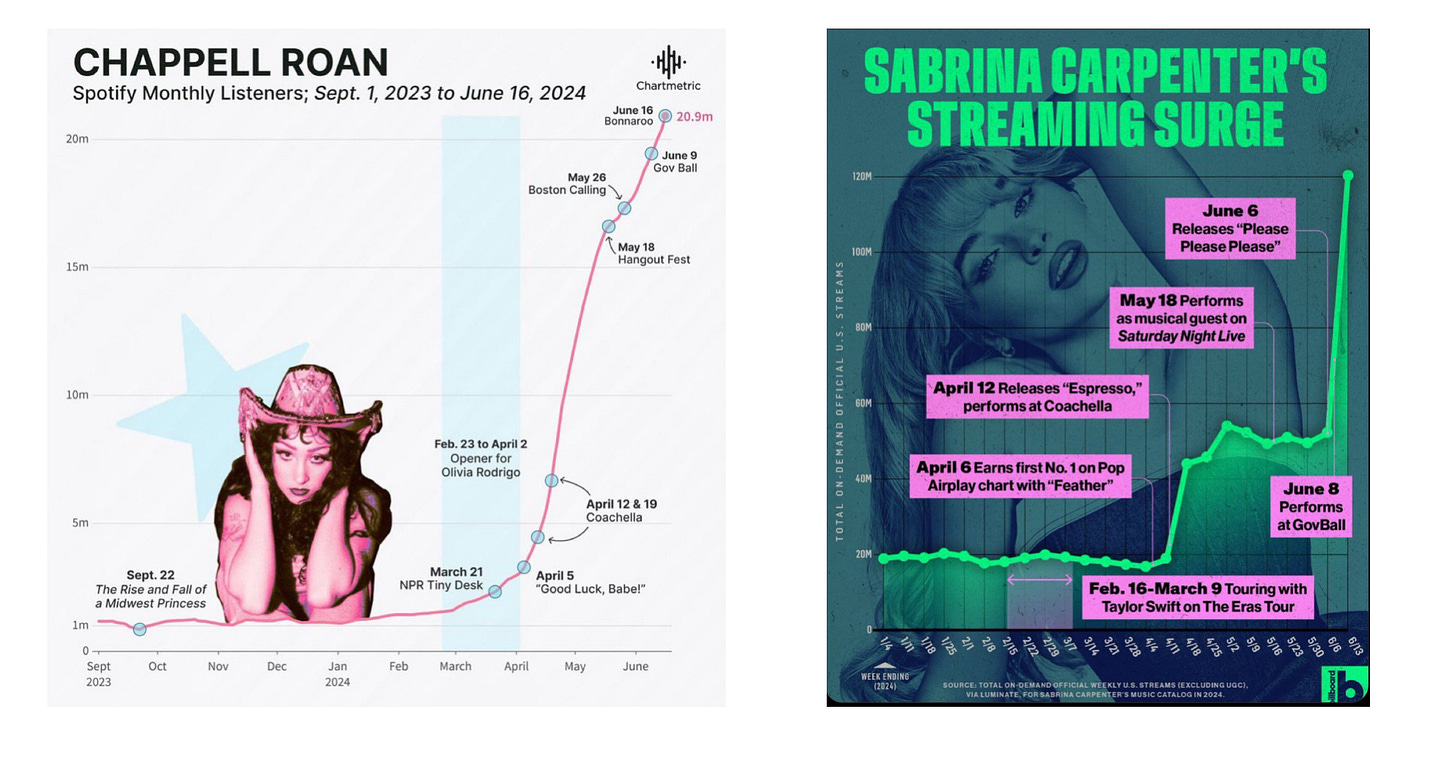

Two of the biggest new US acts this past year have been Sabrina Carpenter and Chappell Roan, who have both seen some impressively monumental shifts in their listenership in the past few months:

These rapid rises (in part created by a system I spoke about in edition 008 of this ‘sletter) are often being seen by onlookers as industry conspiracies; accusations of being an “industry plant” have been thrown at almost every new act that’s come our way lately. The term is being bandied around as far as the eye can see on Twitter, and searches for “what is an industry plant” have reached an all-time high on Google over the past year. I’ll save you the bother:

These suspicions are partly rooted in a deep-seated distrust of the music industry and its machinations, and in the idea that the majors have some kind of special lever to pull, to make the people they want to make famous, at the precise time they want them to succeed. A dream scenario for a label, but sadly just not true.

Today’s industry plant is yesterday’s “sell-out”, which for a time was the ultimate pejorative to aim at a musician. Where sell-outs would get to the top and then make decisions that didn’t seem to align with their outward projections, now we question how they got here in the first place and if they deserve it. We ask the same across industries: the uptick in industry plant chat also coincides with the term “nepo baby” which emerged in 2022 as a dig at Judd Apatow’s actress daughter, Maude.

Sometimes accusations of being an industry plant can be downright misogynist or racist, but mostly they’re just misguided. Our current system turns out artists that look like overnight successes, especially when you hit the algorithm jackpot. But mostly, people aren’t following the years of build-up, the empty gigs, the songs that don’t do well, especially when the history of those things gets wiped online as soon as the act gets big and their brand starts to take hold.

Chappell Roan was captured crying at a recent gig, saying “I feel a little off today, because I think my career is going really fast and it’s hard to keep up”. And that’s the reality for the average listener, too - it’s hard to keep up, and the splintering of culture has left many people with a lack of imagination about what might be popular in 2024. The industry plant slur can often smell of “if I haven’t heard of them, how can they be so popular?”. In 2024, that’s true of almost every act on the chart.

But, the truth is there is a lot to be skeptical or even angry about. Our thoughts on industry plants might reveal our buy-in to the American Dream - that it is the pinnacle of virtue to have started from nothing. We want to think The Dream is at once possible, but also hope that it’s not - so that we can judge others’ successes based on the leg-up they have had and absolve ourselves from not making it. We’re also morbidly looking around to see who we can cancel, to see who doesn’t deserve the riches they have got.

In many ways it feels harder than ever to fake it in the music industry or, at the very least, more expensive and time consuming. But all in all, it’s pretty understandable that we might have reached peak skepticism.

Artists couldn’t previously afford to buy up proverbial lottery tickets by releasing incessantly, or releasing sub-par music that might still garner some passive streams. Now, some people are making good money from uploading literal silence or generative ambient music onto Spotify under countless faceless accounts. This New York Times piece explored the career of a man who makes his money by uploading tracks whose titles are the names of real people, and made nearly half a million dollars on songs about “poop, puke and pee.” It’s an SEO cashgrab in the era of Alexa, and a pretty smart one. Whilst making bank from songs about sh*t isn’t a crime, - there’s obviously a market for it, and a skill in what he’s doing - there was a recent story about a man in Denmark who was sentenced to 18 months in prison for using bots to inflate his streams. His fraudulent streams and copyright violations (for speeding up tracks he didn’t own) had earned him over $600,000 when he was caught.

Now, some of this we would only categorize as music in the technical sense: it’s music in the same way that a “Live, Laugh, Love” sign is art. Most people know how to spot the difference, but the overall effects of streaming fraud and the idea that you can game the system play into a general atmosphere of subterfuge.

It’d be naive to think that labels aren’t knowingly playing this game too - streaming farms are a well-known form of modern payola, and the outdated obsession with chart positioning has led to some intriguing marketing tactics. Taylor Swift’s latest album, The Tortured Poets Department, is 31 tracks long - an interesting creative decision, if not a more interesting decision for just buying what feels like “market share”. It’s a cynical take, but it’s backed up by the release of more than twenty iterations of the vinyl. Perhaps they’d wager they were “superserving fans” or “serving superfans”, but you might also suggest they’re creating a music monopoly partly based on being able to dominate the charts for weeks and months in a row, sometimes based on technicalities alone. It’s not just about gaming the charts, but also the space of public opinion.

Last summer, unknown country artist Oliver Anthony released “Rich Men North of Richmond”, and was furiously and curiously supported by conservative politicans and media who wanted to boost the lyrical content of the song - complaining about taxes and welfare recipients. After a concerted buying effort, his single bounced to the top of the iTunes download charts, and translated into real success for Anthony, in what felt like a real convergence of music with political astro-turfing.

Devoted K-pop fans have been well known to organize successful group efforts to game the charts, and have even done some impressive activism as a collective. Though people have used the word astro-turfing to describe this behaviour too, it’s really just the extreme end of fan buy-in. This kind of unwavering support and fan fervour is a golden ticket for most artists and labels, and it’s extremely hard to manufacture.

Billboard recently announced the “Billboard Hot 100 Challenge”, in which participants listen to a new song daily and guess the ultimate peak position of the song on the charts. At the end of the season (July, if you’re thinking of entering), the first place winner gets $25,000. There’s a few reasons Billboard might set up this kind of venture, but outside of their gains, it does in some sense help to tie fans to the success of an act without having to spend anything. Perhaps the #1 will also end up with a job as an A&R.

In many ways, all of these gaming behaviours are responses to the demands of the marketplace, jockeying the algorithm to get to the real meat of the sandwich: ticket sales.

Much of what people might define as “industry plant” behaviour is just plain-and-simple marketing dollars. For instance, Spotify’s Discovery Mode (which is a pay-to-play feature that puts your track in front of new listeners who, according to their data, might be interested) has caused some people to be suspicious, since it’s forced in front of them. Ultimately, it’s pretty much the digital version of paying for a radio campaign.

But as onlookers, people are aware and more importantly suspicious of the mechanisms behind the makings of a modern pop act now. People know what the bot accounts look like, the fake fans, the planted “news” stories, and that the quickest way to the top is to scam (as Jia Tolentino said in her essay on scams in Trick Mirror).

We search for the authentic within the fakery we get on a daily basis - from “Scam Likely” calls to deepfakes to online courses made by your average Joe. All of our platforms have been gamed: from Amazon reviews to Google reviews, and even Goodreads reviews. We watch infinitely regurgitated content on social media, without always being sure of the source. We listen to AI diss tracks, and aren’t quite sure if they’re AI. Some big name artists, like Ne-Yo and Fat Joe, have even been called out for their own mixtape feature or playlist scams that target up-and-coming acts. So it’s understandable we’re on high alert at all times, and yet also fascinated by the people who dare to try it on, from Elizabeth Holmes to Anna Sorokin.

With the latest convergence of AI and hustle culture, skepticism for skullduggery is taking a new turn. It’s part of the reason why someone like Charli XCX is winning in the cultural space right now with BRAT. She has an astute meta awareness of stardom and marketing in both her music and her campaign. It feels honest to its core, it’s artist-led, and it’s culturally and aesthetically interesting - which is how you end up creating the zeitgeist of 2024:

Anyway, in the end, there are no winners and losers in music. Only creators.

Just kidding. Honestly, I myself have spent a lot of time trying to help artists game the system. The smoke and mirrors can be part of the fun, especially if you’re the ones making it happen. Part of it is supposed to be theatre, so perhaps we can just suspend our disbelief and try to enjoy the show?

And honestly, you can pay for all the fake stuff you like, but in the end, you really cannot fake the funk. My attempts at making music on Suno have categorically proven that.

And lastly, some random things I’ve enjoyed lately:

The final Keysound show on Rinse FM. A staple for forward UK club music over the past 17 years. Salute!

This recording from a 1980’s “Kingston’s most storied skate park” (in Jamaica) on NTS.

This Iceboy Violet & Nueen video, out on Hyperdub. Trigger warning: this video was made with AI.

This “minimal beat machine” that you play with in the browser.

Couples Therapy on Showtime.

Just in case there are also tennis nerds like me reading this, this Atlantic piece on the dying one-handed backhand.